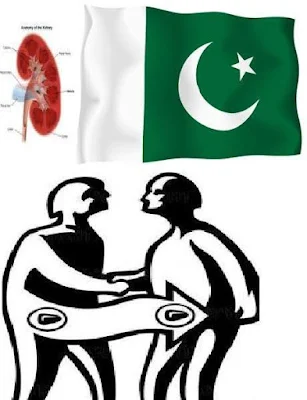

Reader Tariq alerted us to the Pakistani auction website Bolee.com, whose front page (yesterday) was advertising a “Kidney for Sale” (there were three Ads for this, but all from the same person). Search for the website on Google and you will see a bold “Welcome to Pakistan’s First Auction Site.”

There are, of course, a number of other Pakistan auction website, some seemingly having much more to offer but, luckily, no kidneys. We have carried a post in the past about someone wanting to sell his kidney to make ends meet, but this Ad on the auction website raises so many issues and questions that one is left speechless!

Luckily there were no bidders on the kidney when we checked (and captured this page image). The description read:

I am 26 year old healthy person & want to sellout my healthy one kidney for AB+ compatible person, My demand is Rs.600,000(Operations & other medical expenses”ll be beard by kidney purchaser).

Frankly, its too distasteful a predicament for one to find the Pinglish in this description (“year”, “sellout”, “healthy one kidney”, “expenses’ll”, “beard”) funny.

This is not just about an internet site and a rather ridiculous, maybe frivolous, notice on it. The problem is real. And the problem is much bigger.

For example, a recent scholarly article in Transplant International by researchers from the Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation (SIUT) points out that Pakistan has now emerged as one of the largest centers for commerce and tourism in renal transplantation:

In recent years, Pakistan has emerged as one of the largest centers for commerce and tourism in renal transplantation. Kidney vendors belong to Punjab in eastern Pakistan, the agricultural heartland, where 34% people live below poverty line. We report results of a socioeconomic and health survey of 239 kidney vendors. . Ninety per cent of the vendors were illiterate. Sixty-nine per cent were bonded laborers who were virtual slaves to landlords, laborers 12%, housewives 8.5% and unemployed 11%. Monthly income was $US15.4 with 11 dependents per family. Majority (93%), vended for debt repayment with mean debt of $1311.4 . The mean agreed sale price was $1737. However, they received $1377 196 after deduction for hospital and travel expenses. Post vending 88% had no economic improvement in their lives and 98% reported deterioration in general health status. Future vending was encouraged by 35% to pay off debts and freedom from bondage. This study gives a snapshot of kidney vendors from Pakistan. These impoverished people, many in bondage, are examples of modern day slavery. They will remain exploited until law against bondage is implemented and new laws are introduced to ban commerce and transplant tourism in Pakistan.

The authors of the article, including the head of SIUT have since launched a very worthy campaign against the illegal and inhuman trade in kidneys from Pakistan and all the ways in which this exploits the already poor and vulnerable. There is talk now of a law to legalize such trade and in the rush to focus on the so called “benefits” of selling one’s vital organs, there is little attention on what this means for those whose poverty will make them the victims.

Health experts are concerned about Pakistan unregulated and fast growing kidney transplant trade, where foreigners can buy kidneys from impoverished Pakistanis in contravention of established medical norms. With more than a dozen hospitals across the country involved in this unscrupulous trade, Pakistan has become the new Mecca for people seeking kidney transplants from across the world.

Transplants are a lucrative business for Pakistani doctors, hospital staff and fixers who exploit the gullible and the needy. So much so that in some Pakistani villages, most people survive on one kidney. In Mominpura village in central Punjab, nearly 80 per cent of the residents have sold one of their two kidneys. Only children, the old and the sick have been spared the scalpel. “Anyone above 16 is taken to a hospital for a possible transplant,” claims a villager.

According to people involved in the kidney trade, besides Pakistan, China is the only country in the world where illegal and unrelated donor organs are transplanted. In China, kidneys are taken from prisoners on death row. “Any transplant that is unrelated is unethical,” believes Dr Anwar Naqvi, a senior surgeon at the Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplant (SIUT) in Karachi. Naqvi is campaigning against unrelated transplants in Pakistan.

Take 22-year-old Sumaira of Mandiala Wala village located 30 kilometers east of Lahore in Punjab province. She is no different from the hundreds of villagers here learning to live on one kidney. In Sumaira case the choice was not easy. She and her family could either stay in bondage for life to a brick kiln owner, or she could sell one of her kidneys and pay off the family mounting debts. Sumaira decided to donate. In January 2002, she was brought to a hospital by her parents.

The staff conducted pre-operative tests on Sumaira and she was sent home after signing an agreement with the hospital management to donate one of her kidneys. A month later, she was summoned by the hospital: a recipient had been identified.

In the clandestine kidney market, if a kidney is sold to a local recipient, the donor gets US $1,600 but if sold to a foreigner, the payment is double. As a goodwill gesture, the recipient is introduced to the donors before the transplant. But in Sumaira case, her 32-year-old recipient, Thor Anderson, a property developer, born in Denmark and living in London, avoided meeting her due to the prevailing anti-West sentiment over the Iraq war. Of the US $3,200, Sumaira family used US $1,600 to repay loans. Over US $500 went to a broker, with US $250 spent on post-operative care. They were left with US $750, a sum that didnot last long, considering Sumairalarge family. It is now her brother turn to join the long queue of poor donors willing to sell a kidney for money. This is not risky at all,†Safdar contends.

In the West, the vast majority of donor kidneys are taken from people killed in accidents. But as the number of patients has spiraled the world over, the transplant business in poor countries continues to expand. Also, in some countries, as in the UK, recipients have to know the ‘live’ donors, and cannot pressure them. This makes legal transplants difficult in such countries. Patients, therefore, travel to poor countries where there are either no laws or no regulation.

Sadly, most people are no better off after the sale despite the risks. Sughra Begum sold her kidney for just US $1,300. Her husband, Muhammad Yar, had also donated his kidney four years ago to repay a loan from their landlord, but the middleman made off with the money.

That is when Sughra decided to sell her kidney. Though they managed to repay the landlord, the operation took a toll on her health. Due to her constant illness and her husband a critical condition, they were forced to take another loan and are back in their landlord clutches.

According to data compiled by the Pakistani organization, Postgraduate Doctors Middle East, in the year 2001 there were 1,244 kidney transplants, of which relatives donated 611, spouses 80 and unrelated donors 533.

Due to an increase in donors, several hospitals have started offering less for the kidneys.

SIUT Naqvi dreads the future. “The very wealthy will end up as buyers of the organs being sold by the very poor. Such an unequal distribution of health benefits and burdens will be completely unjust,” he says.

When people become compelled to sell their vital organs on the internet or to unscrupulous traders, it says volumes about just how vulnerable their lives and livelihoods have become? It says as much, or more, about the society that allows this to happen? But does anyone in our society care?