Suttee could not just be abolished overnight. As its association with myth suggests, it was deeply rooted in the culture. It goes back to ancient times among various peoples, with instances recorded among the Thracians, Malaysians and others. An early account of its enactment by Indian widows appears in the Greek historian Diodorus, where it is dated as occurring in 317 BC (Yule and Burnell 879). Besides noting its connection with the goddess Sati, the Victorians held various theories about it. The most sympathetic was that it started from "the voluntary sacrifice of a widow, inconsolable for the loss of her husband ... solely because her affection to the deceased made her regard life as a burden no longer to be borne" (qtd. in Peggs, India's Cries, 3rd ed., 214). But some saw cruelty in it from the start, suggesting that it arose from "a dread on the part of the chiefs of the country, in olden time, that their principal wives, who alone were in possession of their confidence, and knew where their money was concealed, might secretly attempt their life, in order at once to establish their own freedom, and become possessed of the [i.e. their husbands'] property" (St John et al., 489). Whatever the origin, other ideas had gathered around the practice — for example, that those who chose to die in this way not only displayed wifely virtue at the time, but would continue to serve their husbands in the afterlife; and, still more curiously to western observers, that the woman's action would expiate the sins of her husband's family. Such ideas had produced a cult predicated on suttee's "magical efficacy," as one social historian puts it (Weinberger-Thomas 168), but at the same time left the custom open to abuse. Instead of being a matter of choice, suttee might be enjoined, the woman cruelly coerced by those who stood to gain by her death, whether the gain lay simply in family honour, or in more tangible assets.

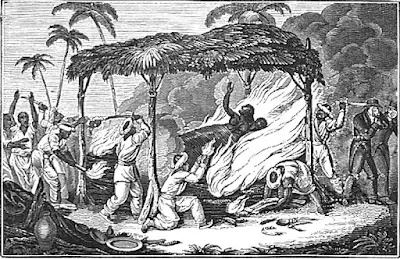

Western observers were apt to interpret suttee in their own way. There is no question of coercion in this next picture. The voluptuous woman gazes raptly at the corpse of her husband, while musicians perform in the left-hand corner. Drums and other instruments were indeed played on these occasions, reportedly to drown out any groans or screams of agony. "It is a fatal omen to hear the suttee's groan" (qtd. in Yule and Burnell 883). But this scene has an almost carnival-like atmosphere. It is a sexed-up version of events, in which only the person in the far right of the foreground, with face hidden, seems distressed. In exchange for letting the ritual go ahead, Warren Hastings, Governor-General of India from 1732-1818, and the prelate to whom he is talking in the upper right-hand corner, are receiving bags of rupees — despite the fact that Hastings himself describes the whole thing in the speech bubble as "shocking to humanity." How far can we trust Rowlandson here, bearing in mind his unlikely depiction of the widow? Hastings was certainly dogged by allegations of corruption, and eventually impeached (though acquitted), and he believed in respecting Indian ways. But he is reported to have said later that he would have abolished the practice "if he could have relied upon the popular feeling being in his favour in our own country," explaining that "the danger [of interfering with Hindu customs] was felt, not in India, but only in England!" (Peggs' emphasis, in India's Cries, 3rd ed., 253).

No comments:

Post a Comment