Lately, a message is being posted and circulated by supporters of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf, that attempts to strike some semblance between Imran Khan and M. A Jinnah.

While a strong liking may be taken to it by those politically aligned with PTI, but to those who are just reasonably au fait with history and Jinnah’s life, it is seen as an obnoxious distortion of and selective display of facts; which must be set straight.

In a sincere effort to put together a relatively, factually accurate rebuttal; this post relies heavily on excerpts from the magnum opus on Jinnah: Stanley Wolpert’s ‘Jinnah of Pakistan’.

And so it commences:

1. Contrary to what the altered versions of this viral post/status say, Jinnah never in his life, attended Cambridge University or any other university, leave alone having been enlisted in a ‘Hall of Fame’ of some educational institution in England. He only completed his legal education there. How someone could so callously come up with such a fallacy is beyond logic.

[1]

*Mamad was what Jinnah was lovingly called in his family.

[2]

Jinnah was later enrolled at Sindh Madressa-tul-Islam.

At a young age, his aunt Manabai took him with her to Bombay, (where uncertainty casts doubt on whether he attended Muslim Anjuman-I-Islam over there or Gokul Das Tej Primary School). After which, he was brought back to his parents who registered him at the exclusive Karachi Christian Mission High on Lawrence Road.

[3]

In that period, the flourishing business of Jinnah Poonja (the Quaid’s father) had come to be associated with Douglas Graham and Company, whose General Manager Sir Freidrick Croft who ‘obviously liked Mamad and thinking highly of his potential to recommend the young man for an apprenticeship to his home office in London in 1892’.

In that period, the flourishing business of Jinnah Poonja (the Quaid’s father) had come to be associated with Douglas Graham and Company, whose General Manager Sir Freidrick Croft who ‘obviously liked Mamad and thinking highly of his potential to recommend the young man for an apprenticeship to his home office in London in 1892’.

[4]

After his travel to London, it was on April 25th 1893, that Jinnah ‘petitioned’ Lincoln’s Inn and was granted permission to be excused the Latin portion of the Preliminary Examination, which he passed on May 25th .

After his travel to London, it was on April 25th 1893, that Jinnah ‘petitioned’ Lincoln’s Inn and was granted permission to be excused the Latin portion of the Preliminary Examination, which he passed on May 25th .

Wolpert pertinently states:

‘Had he procrastinated he might not have been able to complete his legal apprenticeship, for the next year a number of prerequisites were added and the process of professional legal certification was substantially prolonged.’

While in England, Jinnah was influenced and fascinated by the fresh British liberalism and it was there, that he was presented with a glance in the fascinating world of politics. He often visited Hyde Park and the visitor’s gallery at Westminister’s House of Commons.

[5]

Due to a rather dramatic turn of events (paronomasia intended: Jinnah had developed a passion for theatre in London, and had sent a letter to his father to allow him to participate in it – only to be reprimanded and summoned back) Jinnah had to return back to British India after applying for a ‘certificate’ from Lincolns’ Inn:

Due to a rather dramatic turn of events (paronomasia intended: Jinnah had developed a passion for theatre in London, and had sent a letter to his father to allow him to participate in it – only to be reprimanded and summoned back) Jinnah had to return back to British India after applying for a ‘certificate’ from Lincolns’ Inn:

Due to a rather dramatic turn of events (paronomasia intended: Jinnah had developed a passion for theatre in London, and had sent a letter to his father to allow him to participate in it – only to be reprimanded and summoned back) Jinnah had to return back to British India after applying for a ‘certificate’ from Lincolns’ Inn:

Due to a rather dramatic turn of events (paronomasia intended: Jinnah had developed a passion for theatre in London, and had sent a letter to his father to allow him to participate in it – only to be reprimanded and summoned back) Jinnah had to return back to British India after applying for a ‘certificate’ from Lincolns’ Inn:

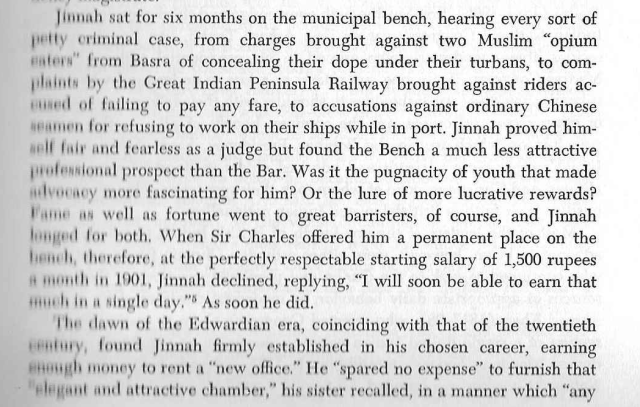

|2|. Nothing more could be more further from the truth than the view that Jinnah ’suffered severely at the start of his legal career’ .

Upon his return, the realization of his mother’s death and his father’s sinking business, which had been subject to the whims and vagaries of time, dawned upon him dealing him a dark stroke but eventually, Jinnah did climb up the ladder professionally and out of this sombre chasm.

[6]

|3|. The ‘Flower of Bombay‘ that blossomed in Jinnah‘s heart had converted to Islam becoming Maryam from Ruttie, three days before their marriage on Friday April 19th, 1918. [7]

And although Ruttie and Jinnah’s story was a Shakespearan tragedy, and their marriage eventually withered but they did not divorce.

‘Her health continued to deteriorate; from 1926 through 1928 she was restricted mostly to bed.

Accompanied by her mother, Ruttie went to England in 1928 and later to Paris where she was admitted at a clinic in Champs Elysee. She was in a semi-comatose condition there …

Mohammad Ali Jinnah went to Paris and stood by her side, even eating the same food she was given. Ruttie’s health improved and she moved to Bombay where it took a turn for the worse again.’

An outstanding video comprising painstakingly compiled quotes and excerpts, weaves a silent narration of this entire so beautiful, yet so heartbreaking tragic love story.

|4|. As Jinnah and his wife had never divorced, the idea perpetuated by PTI’s page that Dina Jinnah’s custody was awarded to her mother by a judge, is naturally overturned.

Little is known of how and where Dina stayed during the years of her parent’s separation and after her mother’s demise.

But Wolpert mentions her at the time of Jinnah being at the peak of his political engagements at the age of 55, which means that the year must either be 1931 or 1932:

[8]

Jinnah also maintained formal correspondence with Dina, even after her marriage to Neville Wadia that he was in opposition to.

He addressed her as ‘Mrs. Wadia’ throughout it.

|5|. To roughly cram Jinnah’s first few years in politics as a ‘failure’ is not only harsh, but a travesty.

There is nothing that suggests his political penury during the years of 1900s, when he stepped into the domain.

And there is much that can be used in rebuttal of this, but for the sake of brevity, the following excerpts should suffice.

At the beginning of his political career, Jinnah simply remained a keen observer of and judiciously analyzed the course of events in British India while closely following figures like Dadabhai Naoroji and Sir Pheroze Shah Mehta – on whom he was not unable to leave a favorable impression.

[ 9]

Jinnah had joined the Congress in 1906, and later the Muslim League in 1913.

The belief and notion of a single Indian nation regardless of religion, which recurred in Mehta and Naoroji’s speeches, reverberated strongly in Jinnah’s stance and thoughts; eventually earning him the respected title of ’Ambassador for Hindu-Muslim Unity’ in 1916, after his role in the formation of the historic Lucknow Pact – a common ground for cooperation between the Muslim League and Congress for accomplishing gains in the bid for self-government for British India. (Jinnah presided over the joint party session in Lucknow).

The belief and notion of a single Indian nation regardless of religion, which recurred in Mehta and Naoroji’s speeches, reverberated strongly in Jinnah’s stance and thoughts; eventually earning him the respected title of ’Ambassador for Hindu-Muslim Unity’ in 1916, after his role in the formation of the historic Lucknow Pact – a common ground for cooperation between the Muslim League and Congress for accomplishing gains in the bid for self-government for British India. (Jinnah presided over the joint party session in Lucknow).

How all that comes down to evolving into failure, is rather a very difficult conundrum.

[10]

|7|. Exactly to which era of pre-partition history that was intended to indicated towards through the point ‘Won only 1 seat after a decade of struggle’, is unclear but in retrospect the year of Jinnah’s ‘solemn’ involvement and foray into politics, which is largely-accepted to be 1906, should be considered.

After being bestowed with honorary titles such as the ‘Ambassador for Hindu-Muslim Unity’for the result of the culmination of his and others efforts to ensure union between the two parties, four years after 1906, in 1910, he was elected to the Imperial Legislative Council. (Bear in mind, Jinnah was only a member of the Congress at that point in time, neither a party leader nor part of the Muslim League.)

[11]

|8|. The adoption of the ‘Lahore Resolution’, was indeed a most momentous day in subcontinental, and Muslim League history, and in Jinnah’s political life. But how exactly can it be assessed that it was definitely what ’won people’s hearts and minds’ is quite complex and cumbersome to gauge.

So for the purpose of lucidity, it must be assumed that this phrase was meant to imply the complete guarantee and consummate ‘arrival on the political scene’ and success of Muslim League and its future proposals: Pakistan.

So for the purpose of lucidity, it must be assumed that this phrase was meant to imply the complete guarantee and consummate ‘arrival on the political scene’ and success of Muslim League and its future proposals: Pakistan.

Even this is not in perfect accordance with reality, as after his return from London and the fragmentation of the All India Muslim League, Jinnah had diverted all his focus and energies to the strengthening and revamping of the party through critical and massive reorganizing – something which took a toll on his health too.

(‘Towards Lahore’ is an immensely informative chapter centering around this very ’restructuring’ of the AIML in the 1930s)

[12]

The watershed moment at Minto Park on 23rd March 1940, was only a result and culmination of the success of this pivotal political and social rearrangement of AIML.

|9|.There wasn’t really a plethora of or ‘weighty’ parties in Pre-Partition India, if there were any, there were only the Indian Congress and All India Muslim League. Both, which at the end, owing to a twist in situations, stood completely different – on divided soil.

Bottomline is, nugatory and politically pointless parallels need to be stopped being drawn between the politicians of today and the leaders of yesterday.

Emotionalism, exagerration, lack of realism dipped in populism are what deplorably compose ’appeal’ in Pakistan. But still, at the end of the day, 200 million people do not want to know how similar a party leader is with the founder of the country but what a party has to offer them; socially, politically and economically.

Most importantly, please study history before indulging in an utterly distasteful presentation of ‘facts’. And do leave Jinnah out of it, his ideology and vision for Pakistan has been distorted enough to reach the brink that this state is on – kindly spare his life now.

To quote Stanley Wolpert again:

“Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creating a nation-state. Mohammad Ali Jinnah did all three.”

He was not infallible but there was only one Jinnah in Bombay, in sartorial incomparability, peerless finesse and debonair, political brilliance and realism and only one Jinnah of Pakistan. Let us not make him and his life a casualty in and party to political tactics.

![Dina_Jinnah_thumb[2]](https://hafsakhawaja.files.wordpress.com/2012/05/dina_jinnah_thumb2.jpg?w=640)

No comments:

Post a Comment